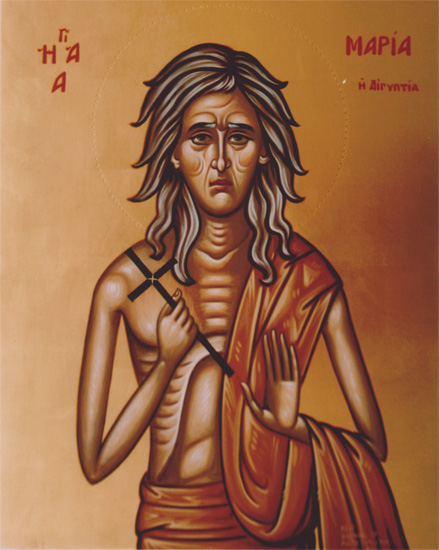

This week of Great Lent, the Church celebrates the memory of St. Mary of Egypt. The story of St. Mary is the story of a repentant harlot. Why does the Church find this story so important? Why does the whole Orthodox world remember this woman?

Her life tells us about how, from her early youth, she carried on an extremely debauched life and then, more like a tourist than a pilgrim, decided to go to Jerusalem for the feast of the Exaltation of the Honorable Cross of the Lord. But a mysterious power would not let her into the church until she became conscious of her sins and called out to the Mother of God and to the Lord for mercy. Then she was able to enter the church, and shaken to the core, resolved to spend the rest of her life in prayer and repentance. Many years later, the saintly monk Zosimas met her in the desert; it is from him that we know her story.

What message—across centuries and countries—does her life give us?

It is the story of finding hope. Mary had a reality, which, for the time being, suited her. As the poet said, “wine and men were her atmosphere.” But she had no future; she only had what one prefers not to think about. Soon her charms would wilt—especially soon due to her unhealthy lifestyle—and men would lose all interest in her, turning their attention to new victims with social temperaments, and she would become lonely, cast off, and lacking means for sustenance. But in turning to God she found hope—hope not only that her earthly life would be filled with dignity and meaning, but most importantly that before her is eternal life.

It is the story of finding dignity. Not long ago, I saw in an atheist internet social network a photograph of pilgrims on bended knee, with comments from unbelievers about how humiliating and slavish it is to kneel. This world considers that repentance is a denial of human dignity—as if during Mary’s depraved street life she was living in freedom and dignity, but when she rose up and went to her Father, she became a slave. The values of this world are turned inside out, and repentance offers a restoration of the true system of accountability.

It is the story of finding love. From the worldly point of view, a person who has gone out into the desert in order to dedicate her days to repentance and prayer must have done it out of bitterness and despair, from the inability to have a “normal” life. Of course, God is not proud—He receives also those who come to Him out of total hopelessness, but more often it is not that way. People become monks who were quite well off by all worldly standards. Why? Because they saw the True Light; something was revealed to them that was so precious and inexpressibly beautiful, that for its sake one can joyfully leave everything behind. Mary met the One Who truly, sincerely, and eternally loves her—as a precious human being, called to eternal life.

This is the story of finding freedom. Traditional society can be considered more moral in some respects—depravity at least did not dare to glorify itself—but in certain respects it was much more hopeless. A “fallen” woman, whose reputation had already been made (and such a reputation could be made very quickly), had no hope of returning to “decent” society. All doors were closed to her, and the only thing she had left to do was to continue sliding down the hill that she had one day incautiously found herself on. Society literally pushed her there: once a harlot, always a harlot, and that’s that. But apparently God does not agree with “decent” society—He stretched forth His hand and completely changed this woman’s life; He made her a great saint, whom the Church has glorified through the ages.

In modern society, the pressure that pushes a once fallen person deeper into the pit is significantly weaker. But it is still very hard for such a person to turn away from the path he’s on. “Drink, and the devil will take you to the end,” as the pirates sing in “Treasure Island”. People sometimes say that they have been “non-religious all their lives,” that they have “sinned too much”, that now it’s “too late to change their lives”, and all they can do is to keep going down the beaten path to the end.

But the story of St. Mary of Egypt reminds us that if you fall into a pit, you are under no obligation to dig in further; and if you slip, you don’t have to slide all the way down to the very bottom. As is written in the Scriptures, Because this is what the Lord says: He that falls, does he not rise up? … and behold, and he that turns away, does he not return? (Jer. 8:4). A person is not obligated to go his whole life along the well-worn rut—he can turn around 180 degrees and change his life. And Great Lent is the time when the Church reminds us about our freedom: we can leave our former sins behind and turn to God.

source:http://www.pravoslavie.ru/

Sergei Khudiev

Translation by OrthoChristian.com